Shakti Pith #28: Kankalitala

Kankalitala: Mandir and Sacred Kund

While at first glance appearing to be no more than a modest rural temple, a closer examination of the Kankalitala Mandir reveals a unique mythology coupled with a vibrant local culture.

The garbhagriha (literally meaning “womb chamber” in Sanskrit) at Kankalitala’s main temple consists of a small room that is capped by a curved pyramidal roof, ornamented with a metal spire. Connected to this is a rectangular raised platform referred to as the natmandir. This natmandir is roofed and serves as an area where devotees can have a direct view of the temple’s main devotional image as well as respite from the sun’s oppressive rays. I observed visiting pilgrims utilizing the natmandir for mundane activities such as napping and quiet conversation, as well as meditation.

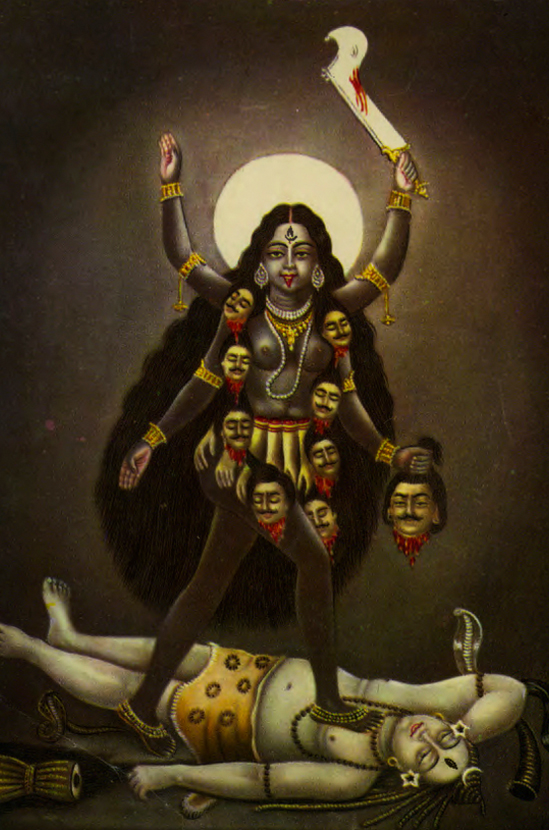

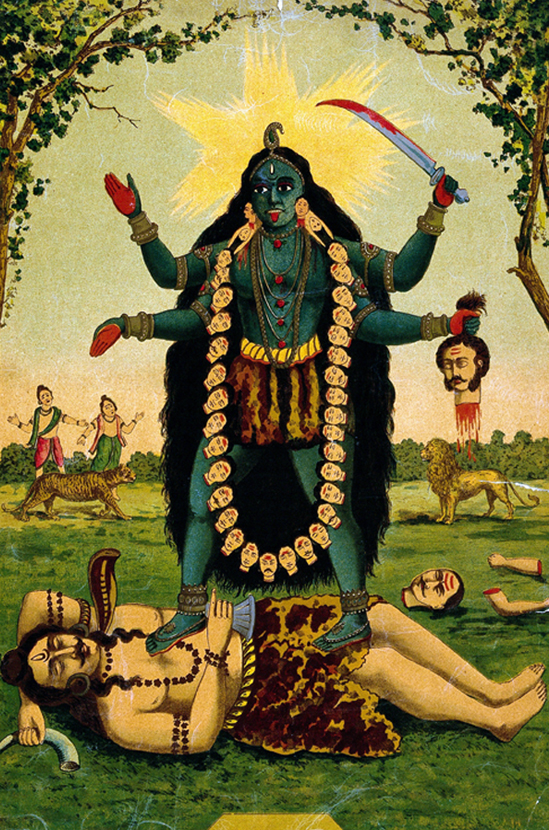

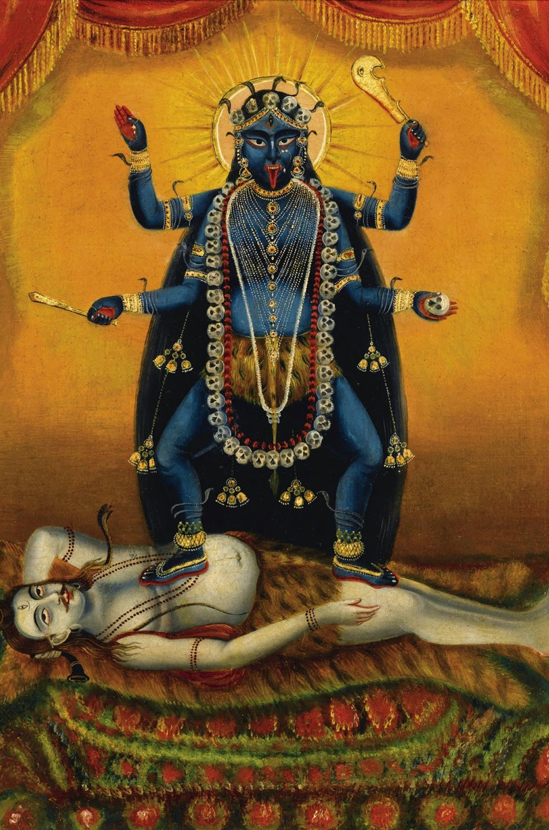

Entering the mandir, I was surprised to see that unlike every other shakti pith I have visited (Kalighat, Tarapith, and Vishalakshi) thus far, the Kankalitala Mandir lacks a three-dimensional devotional image of any kind. Here there is no deity statue made of stone, clay, or metal. At Kankalitala, the image that is attended to by the purohits (Hindu temple priests) is a framed painting depicting the goddess Kali standing on top of her husband Lord Shiva. There appears to be some conflation with Kali and the goddess worshiped here who is referred to as Kankali. I am inclined to suspect that this evolved quite simply from the name “Kali” being contained within the longer name of “Kankali.” While visiting this mandir, I heard exclamations of both “Jay Ma Kali!” and “Jay Ma Kankali!,” or “Victory to Mother Kali” and “Victory to Mother Kankali!” respectively. At any rate, in the realm of personal devotion, these particulars mean very little for those who come to venerate the goddess at this mandir. When I asked a temple priest if the goddess worshipped here was properly named Kali or Kankali, he responded by saying that both of these names are used to describe the same mother goddess—Ma. This is a very common notion found while researching goddess devotion in West Bengal: all of the different names and forms one comes across describe a single, universal mother goddess—the Great Goddess, or Mahadevi.

Even though the centrally-placed icon of Kali located within the mandir appears to be the focus of Kankalitala, the most sacred object present at this shakti pith is without doubt the kund (Sanskrit for “sacred tank/pond”) located next to the temple. This kund is a small shallow pond that is surrounded by a protective concrete wall topped with red fencing. Next to the temple, this barrier is open and steps lead down to the kund’s sacred water. The kund is in fact the original form of the goddess at Kankalitala: a pond which has been worshiped since ancient times. It is here that Ma Sati’s waist (in Bengali, kankal) is said to have fallen countless aeons ago when her dead body was skillfully dismembered by Lord Vishnu using his discus weapon–the Sudarshana Chakra.

Throughout the course of my visitations to Kankalitala, I asked many people—temple priests, visiting pilgrims, busking musicians, and local shopkeepers—where the actual body part of Sati is now located. I assumed that like the other shakti piths I have visited, there would be a stone adi rup (original form) corresponding with the fallen body part, which in this case would be Sati’s waist. Invariably the answer I received was that when Sati’s waist landed at Kankalitala, it created a depression in the earth which later filled up with water and formed the sacred kund. I was repeatedly told that the actual body part now lies underneath this water. I cannot help but wonder if at the bottom of the kund there may be some sort of rock formation corresponding to the fallen body part of Ma Sati. It seems likely that an isolated, shallow pond such as the Kankalitala kund would periodically dry up during periods of draught, exposing the bottom. If and when this does occur, is an object revealed that was the initial source of attraction for ancient people to this sacred site, or is the Kankalitala kund merely a pond that has acquired sacred status for reasons unknown?

On the opposite side of the mandir, one finds a sacred tree. Immediately noticeable are the numerous stones that have been tied to it by visiting devotees. This is a Bengali folk tradition associated with fertility: rocks are tied to trees as votive offerings to secure both pregnancy and a safe childbirth. While photographing these hanging stones, a man tapped me on the shoulder and directed my attention upward by pointing his finger. Looking higher up into the tree I saw a curious formation which the man told me was a Shiva lingam. Examining my photographs later I noticed a decaying wreath of marigolds that had been placed around it some time ago.

Next to this sacred tree is the temple’s harikath—a device used for the ritual sacrifice of goats. The animal’s neck is placed within the harikath’s wooden fork and secured with a pin. Then, with one swift chop of a ritual sword (called a khadga), the goat is decapitated. To protect the swinging sword from damage, the bricks surrounding this harikath have been removed from the pavement, exposing the soil underneath. It is notable that this exposed area forms a descending triangle with the harikath at its center. This descending triangle shape is often associated with goddess worship where it is symbolic of the yoni, or sacred vulva.

The Smashana

Not far from the mandir’s front gate, a narrow dirt road leads away from the temple and toward Kankalitala’s cremation ground. Walking along this footpath, one will see numerous samadhis on its opposite sides. These are the grave markers of tantriks and sadhus–Hindu mystics and holy men–who by tradition are not cremated.

Entering the main area of the cremation ground brings you to the place where human bodies are burned. The system for performing this activity here is different than what I have observed previously at such burning grounds as Tarapith and Manikarnika. Instead of the typical temporary construction of a wood pyre which is then set alight, at Kankalitala there are two semi-permanent structures which are utilized. Each is essentially a raised, open platform made from several pieces of metal girder spanning across and secured in place by two short walls. These walls are made of bricks that have been covered over with mud which, now dry, feels solid like fired clay.

During my last visit to Kankalitala, I happened upon a cremation that was taking place, and with permission from the man tending the fire, was allowed to take photographs. Unlike the Dom (an “untouchable” caste typically charged with the task of cremating bodies) I have encountered previously during visits to burning grounds, this man was dressed in the type of black attire typically associated with members of the Aghori sect; he also wore a bright red turban. This leads me to suspect that while being a Dom, he might also be an initiate of an organized mystical traditional. Although few in number, there is a notable Aghori presence at Kankalitala. I cannot state for sure that this man is somehow involved with that tradition, beyond association through proximity. What can be said is that this certainly raises a few interesting questions about the nature of the cremations which take place at this shakti pith.

Bengali Folk Music

When I first approached the mandir, I was delighted to hear the familiar sound of Bengali folk music drifting through the air. The musical culture surrounding Kankalitala is a fairly active one, especially considering that it is a relatively small temple. Just outside of the main gate, you can find musicians as well as members of the Baul sect—a group of itinerant minstrel-mystics native to West Bengal—busking for money and singing spiritual songs.

Underneath a sacred banyan tree not far from the mandir’s main gate, I ran across a musical trio composed of two Bauls and a local man who accompanied them with various instruments. Before them were placed pictures of the Kankalitala Mandir along with an image of the framed Kali painting worshiped inside of it. I also noticed the image of a sadhu who I unfortunately could not identify as well as the famous “mad saint” from Tarapith, known as Bamakhepa.

Having a pair of karatalas (small hand cymbals) with me, I decided to join in. They all expressed enthusiasm at my ability to keep proper time with their folk rhythms and we quickly became friends. After this initial positive experience, I made sure that each day I visited Kankalitala, I spent at least a few hours with these men who were not only very welcoming, but also obviously excited that I was interested in recording them.

When I would spend time with my new friends underneath this banyan tree, I saw that many devotees coming from afar would head straight for the Bauls performing here after first offering puja to Ma Kankali at the mandir and kund. Listening for some time, they would donate a few rupees for the musician’s efforts if they felt so inclined and were able to do so. As I watched this take place, a larger picture began to emerge. A mutually beneficial, reciprocal relationship exists between the visiting pilgrims and the Bauls performing here. For the listeners, knowledge is revealed through the mystical poetry of the songs, while the performers spiritually benefit by transmitting this knowledge during their performance. In both cases, the intent and end result is that of connecting with and serving the goddess who is present at Kankalitala.

A Note on the Recordings

The following audio recordings were a pleasure to procure and I feel a modicum of pride in being able to present a sample of the results here. Despite my best efforts, I often experienced a good deal of frustration when what was turning out to be an otherwise clean recording would wind up completely spoiled by extraneous noises such as dogs barking, loud music coming from passing cars, or someone clapping their hands right next to one of my microphones. While I could have easily taken more control over the recording sessions, my basic modus operandi throughout was simply to position myself near the sound source, adjust levels, press record, and consign the rest to the fates. I felt that it was not my place to tell people they should tone down their expressions of joy, nor did I desire to remove the performers from the temple surroundings and bring them to a quieter location just for my sake. I endeavored to capture an audio snapshot that accurately represented the sonic landscape of Kankalitala as I experienced it. Although the sounds of birds, ringing temple bells, passing vehicles, and people’s conversations can be heard in the recordings I have selected here, I feel that they serve to enhance rather than detract from them.

The first three recordings feature Potai Das playing flute, Jiten providing a drone with his harmonium, and an unidentified man adding rhythmic accompaniment on a khol drum:

The melody of Ami Hrid Majhare Rakhbo, a popular Bengali folk song, played on flute by Potai Das and accompanied with a khol.

Flute and khol drumming recorded near the Kankalitala Mandir.

Flute and khol recorded under a banyan tree near the Kankalitala Mandir.”]

These next three recordings feature Jiten Das singing and playing harmonium, Ananda Baba strumming his ektara, and Potai Das providing rhythmic accompaniment with the khol:

“Who dwells within the heart of the sky?” A meditation on the transient nature of life.

Recorded under a banyan tree near the Kankalitala Mandir.

Recorded under a banyan tree near the Kankalitala Mandir.

On the third day I was at Kankalitala, a female Baul visited the group and I recorded one of her songs:

The singing of a Rina Dasi Baul recorded under a banyan tree near the Kankalitala Mandir.

These last two pieces are instrumental and both of them feature the same lineup: Jiten Das plays harmonium, Potai provides rhythm with the khol, and Andanda strums his ektara.

This track is a traditional melody found in the music of Indian snake charmers:

Recorded under a banyan tree near the Kankalitala Mandir.

And lastly, our closing music:

Recorded under a banyan tree near the Kankalitala Mandir.

This is such an awesome article! And definitely the best sound recordings you’ve collected so far. The photos are of course, amazing too. I enjoyed helping you with this- along with all of your other projects! I Love you!

william….yeta khub valo …..hoyeche….aaro kichu yer sathe add koro….amar subecha tomar sathe roilo…

A wonderful article and photos. I have been there and keep such powerful memory of this special place set amongst the quiet bengali countryside. Thank you for sharing some great baul music too!

Wonderful article. I think that Jiten Das and others can be seen in a short youtube clip. Please look here if interested…

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iW47Zb4BpJk

PS. Your site is an inspiration!!!!

can you remove my email above… sorry!!! Wrong Field!

Thank u and extraordinary. Since 14 years i am associated with this sakti pith and have my little asram and dhuni in shamsan. This site will focused about ma kangkali around the world.Thank u once again .

IAm Palash Das Bairagya Abbrash Muluk

Hi Far and Iam Akash Das Bairagya Joy Maa Kalier joy

maa ke darshan kar man bhut perasan huha

That is my boning place and I love that place. Every body say “Joy Ma Kankali”

Actually i want to give more information about kundu.During summer time once in 10-12 years the kundu dries up.That time the kankal can only be visible. Then the devotees clear the pond in bengali term(Pank Poriskar).There is saying that there are several hidden tunnels there which fills up the pond automatically after that.I was lucky to be in touch with some great persons fro that place, they told me that the tunnels are actually connected with some sacred rivers also.That’s why people here believe that the water of kundu is as sacred as water of Ganges.JOY MAA KONKALI.